Since its release in 1995, Toy Story marked the beginning of Pixar’s recognition as a popular choice for adults and children who loved animation. With a series of blockbuster films that received critical acclaim and widespread appreciation, Pixar established the era of computer-generated animation. One of the critical factors for Pixar’s triumph is its ability to cater to audiences of all ages by weaving stories that are equally engaging for teenagers and grown-ups as they are for children.

Certain moments are not suitable for children, and The Incredibles movie is a prime example of this. It intertwines vibrant superhero action with genuine marital conflict and sobering contemplation of death. The upcoming sequel, set to release in theaters this June, is expected to follow this same approach.

After several decades since their first appearance, Pixar’s characters have become beloved childhood icons for a new generation. Those who were amazed by Toy Story during their childhood years now have kids of their own who are discovering and appreciating the mature themes, intricate references, and industry tricks that have made these films enduring classics. As an adult, you may be astonished by some of these aspects that you may not have noticed before.

The Success of Coco Was Controversial

Pixar’s most recent endeavor has turned out to be one of its most remarkable accomplishments, generating unprecedented revenue and receiving widespread acclaim. Furthermore, it secured the studio its ninth Oscar award for Best Animated Feature. Above all, the citizens of Mexico have welcomed it with open arms, propelling it to become the highest-grossing film in the nation’s history.

Coco had to earn the affection it received from the people of Mexico. During the initial stages of production, the film attracted attention when Disney (Pixar’s parent company since 2006) tried to trademark the term “Dia de Los Muertos” in 2013. Affinity Magazine highlights the public outrage that ensued as a result of a large American corporation attempting to assert ownership over a Mexican cultural holiday.

A Mexican-American artist, Lalo Alcaraz gained considerable recognition for his editorial cartoon “Muerto Mouse,” which drew attention to Disney/Pixar’s mistake. The studio’s initial efforts to make amends involved rescinding the trademark application and hiring Alcaraz as a consultant. However, according to Latinx Spaces, more controversy arose when Twitter users noticed the resemblances between the Coco trailer and The Book of Life, another movie about Dia de Los Muertos produced by Fox in 2014. Despite this, Jorge R. Gutierrez, the director of Book, kindly wished Coco success.

Under the guidance of Alcarez, co-directors Adrian Molina and Lee Unkrich steered the Coco team toward triumph. The movie features an all-Latinx voice cast (a first for a film with such a high budget) and had its world premiere in Mexico, which undoubtedly helped to facilitate its endorsement by the community it portrays. While adults may be aware of the hurdles Coco faced on its journey to success, children will simply enjoy a captivating story that celebrates a marginalized population.

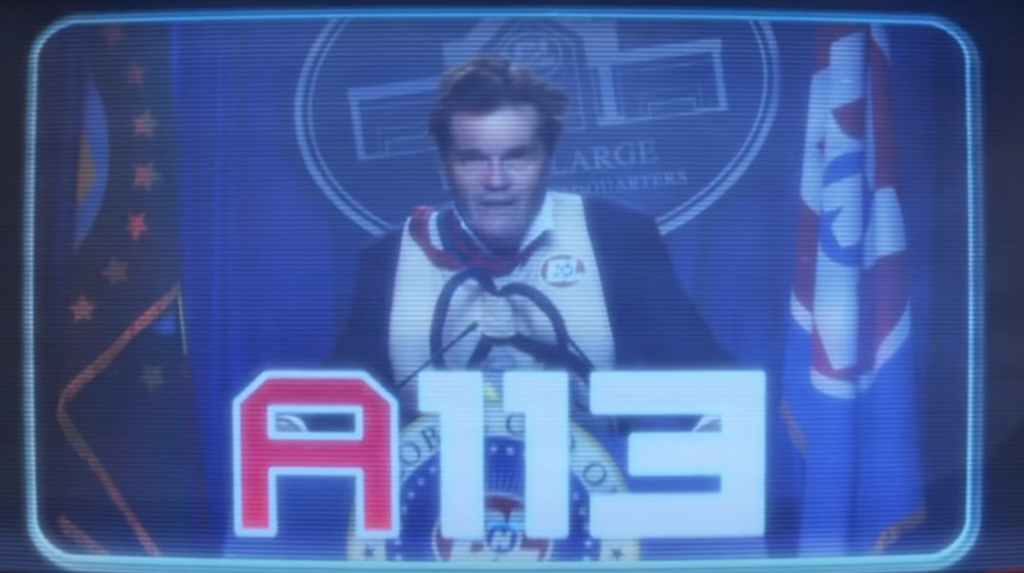

A113 is everywhere

In 1961, a cluster of artists, including Walt Disney, established the California Institute of the Arts. The institution’s animation division would subsequently gain iconic status, providing a platform for budding filmmakers to learn from the pioneers of the craft. The alumni of CalArts have had a profound impact on the animation sector, and each one of them had to go through A113, a legendary classroom.

Vanity Fair featured a piece in 2014 on the CalArts graduates from the 1970s, who would later be credited with spearheading the triumph of Cartoon Network, the renowned Disney Renaissance, and the Pixar phenomenon. A significant number of them had vivid recollections of the character animation courses they took in A113. “It had no door or windows,” recollected illustrator Nancy Beiman, “and the fluorescent lights buzzed incessantly, creating a dead white ambiance.”

It is for this reason that astute fans have spotted instances of this renowned code number in various Pixar films. On some occasions, it may be as inconspicuous as a sign in the background of Up, while in others, it can be as notable as the crucial executive order in Wall-E. And it’s not exclusive to Pixar – A113s have been cleverly integrated into The Simpsons, American Dad, and even The Avengers by CalArts alumni.

A Bug’s Life” Retells the Story of “Seven Samurai

Since its debut in 1954, Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai has been a monumental influence on the film industry. One of its most notable adaptations is John Sturges’ 1960 Westernized rendition of the story, The Magnificent Seven, which has since spawned three sequels, a TV series, and a remake. However, Pixar has also created its own unique interpretation of the classic tale, which has received less recognition.

The plot of Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai revolves around a village that faces repeated raids by bandits after the harvest season. The farmers of the village embark on a quest to find samurai who will protect them in exchange for food. The group they assemble consists of mostly inexperienced or past-their-prime ronin, who then train the villagers to fight back against the bandits.

Pixar’s A Bug’s Life, released in 1998, centers around a community of ants that faces a threat from a group of grasshoppers who demand a share of their harvest. Flik, a misfit ant, embarks on a quest to find help and stumbles upon a group of circus bugs. Misunderstanding them for warrior bugs, Flik recruits them to help defend against the grasshoppers in exchange for food.

Pixar’s A Bug’s Life may not be a direct retelling of Seven Samurai, but the influence of Akira Kurosawa’s classic film is evident. While the movie’s inspiration stems from the Aesop Fable “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” there are parallels in the plot, as demonstrated by a side-by-side comparison at Decider. The story follows an outcast ant named Flik who seeks help from a group of tough bugs to protect his colony’s grain harvest from a gang of marauding grasshoppers. Flik finds unlikely allies in a troupe of circus performers who he mistakes for warriors, and together they train the ants to defend themselves.

Inside Out tackles depression.

Pixar has always impressed viewers with its skill in portraying characters with emotions. From monsters to fish, toys, and even cars, their characters have captured the hearts of millions with their relatable qualities. However, the studio elevated its ability to evoke emotions to a new level with Inside Out, a film that explores the emotions of emotions themselves.

While Inside Out may seem like a fun and thrilling journey through the complexities of human emotions, its deeper meaning is not lost on adults. The struggles of the main character, Riley, to accept her own unhappiness are seen by many as an allegory for depression. Newsweek even featured a group of six child psychiatrists who interpreted the film through this lens when it first premiered in 2015.

Dr. Fadi Haddad commended Inside Out, remarking that he had not seen a film that addressed the emotional aspect of the brain in children like this before. He specifically appreciated how Pixar portrayed the importance of sadness. Dr. Judith F. Joseph concurred, stating that Riley’s story was “fairly precise in terms of the depression symptoms observed in pre-teens.” Although they cautioned that Inside Out should not replace neuro-anatomy in medical school, some of these experts intended to utilize the film as a conversation starter in their sessions.

They love The Shining.

Pop culture references are abundant in modern animated films. Filmmakers enjoy using spoofs and characters from other franchises to attract young audiences, such as in Shrek and The Lego Movie. However, Pixar has a special affinity for a particular film that only adults are likely to recognize. These allusions are typically understated, and it’s not appropriate for children to watch the referenced movie.

Pixar has been including references to Stanley Kubrick’s classic horror film, The Shining, in their feature films since the studio’s early days. While some of these nods are more obvious, such as the iconic carpet design from the Overlook Hotel appearing in Sid’s house in Toy Story, others are more subtle, like the repeated use of the number 237 or the hotel office PA system appearing in Toy Story 3. These references may go unnoticed by younger viewers but are appreciated by adults who are familiar with the famous horror film.

Lee Unkrich, one of Pixar’s prominent filmmakers, is a devoted fan of The Shining and has included numerous Easter eggs referencing the movie in his films. Unkrich has directed or co-directed many of Pixar’s most successful movies, such as Coco, Finding Nemo, Monsters Inc., and Toy Story 2 and 3. In addition to his work, he runs a blog called TheOverlookHotel.com, which he initially started to back up his extensive collection of Shining memorabilia.

Unkrich’s love for The Shining goes beyond simple Easter eggs and references, as he revealed in an interview with Empire. Unkrich shared that he has learned valuable filmmaking lessons from studying Kubrick’s work and incorporating them into his own animated films. He holds The Shining in such high regard that he hopes to one day compile a book on its making, although he admits that finding the time to do so between his work on Pixar projects is a challenge.

Monsters University has a lesson about failure.

Writing a prequel can be challenging, especially when the audience is already familiar with the future of the characters. It can take away the tension and surprise from the story. However, Monsters University manages to deliver a surprising twist in its ending and an unconventional message for young viewers.

Monsters University takes us back to the school days of Monsters, Inc. protagonists Mike and Sulley. Starting out as foes, the movie follows their journey through the familiar settings and conventions of classic college comedies like Animal House. However, by the end of the film, the pressure to excel has left them uncertain about their future career prospects. Although they get expelled, the two friends have bonded. Viewers witness them happily working their way up the company ladder during the end credits sequence, providing a surprising and subversive message for young viewers.

The ending of Monsters University is quite distinct from other children’s movies, and a College for the Win column explains why. According to the column, the movie’s conclusion stands out because it challenges the notion that college is the only path to success. Director Dan Scanlon confirmed this intention in a Huffington Post interview, saying that they wanted to explore a storyline that had never been depicted in family movies before, despite being a common experience for many of us. He further explained that the film aimed to show how people can follow different paths in life, even if they don’t conform to societal expectations.

The Incredibles draws inspiration from the comics industry.

The Incredibles is set in a retro-future world inspired by the 1960s but with a unique timeline. Bob Parr, aka Mr. Incredible, nostalgically remembers a time when superheroes were free from government restrictions. He becomes frustrated with the constraints placed upon him and begins carrying out secret missions. Those familiar with comic book history may notice a parallel between this story and the evolution of the superhero genre.

In 1954, psychiatrist Fredric Wertham wrote a book called Seduction of the Innocent, which linked comic books to juvenile delinquency. As a result, publishers created the Comics Code Authority, a self-regulating organization similar to the film industry’s MPAA. By the 1970s, a revolt against the Code was gaining momentum with the rise of the “Underground Comix” movement and Marvel’s stories that tackled drug-related issues without the Code’s approval. Just like the Incredibles family, creators were determined to follow their own moral compasses.

According to writer/director Brad Bird, he did not have any particular comic books in mind while creating The Incredibles, but the similarities between the film and the comic book industry are noteworthy for fans of superheroes. Interestingly, the Comics Code was officially abolished just after the turn of the new millennium, which coincided with the release of The Incredibles in cinemas.

The parallels between Ratatouille and Pixar’s relationship with Disney

Pixar is widely associated with Disney, as the latter has been the distributor for all of Pixar’s feature films. Pixar’s beloved characters are a regular presence at Disney parks, and their stories are considered to be on par with Walt Disney’s classics. However, it wasn’t until 2006 that Disney and Pixar fully merged, and it almost didn’t happen. As the original contract between the two companies expired after the release of Cars, the renewal of the partnership was uncertain.

Pixar faced a dilemma between creative independence and financial security when its contract with Disney expired. Disney was eager to acquire more Pixar content for their library, but Pixar was concerned about retaining control over the characters they had created during the partnership. This dispute occurred during a turbulent period for the Disney Company, as explained in an article by Mari Ness for Tor. Ness also highlighted the link between these negotiations and the development of Pixar’s film in progress, Ratatouille.

The theory that Ratatouille serves as a metaphor for Pixar’s relationship with Disney has been speculated by fans. According to this theory, Pixar is represented by Remy, who draws inspiration from Auguste Gusteau, who represents Walt Disney. Gusteau’s once-iconic restaurant, which symbolizes the Disney Company, has lost its luster and is surviving by producing mass-produced frozen entrees. It reflects Disney’s practice of churning out direct-to-video sequels in the 1990s.

The notion that Ratatouille may contain an analogy for Pixar’s association with Disney has been the subject of conjecture among fans. However, the movie’s creators have never confirmed this interpretation, which suggests that Remy and Linguine’s partnership reflects Pixar’s requirement for a reputable representative to showcase their concepts. Those who are not interested in the inner workings of the animation industry will simply appreciate the film for what it is: a tale about creativity and the delicate balance between commerce and ardor.

Wall-E is their most political film.

In a year of elections, it’s not uncommon to perceive political overtones in any form of media, whether or not they were intended by the creators. In 2008, during a highly charged political climate with Barack Obama and John McCain vying for the presidency and George W. Bush’s presidency coming to an end, Pixar’s Wall-E made its way to the big screen. The film, which is their most overtly satirical work to date, could be viewed as having political undertones.

The critique of capitalism in Wall-E, a film distributed by the Walt Disney Company, may appear contradictory, but it is an unmistakable part of its message. The movie depicts a future where mountains of waste, created by consumerism, have rendered the Earth unlivable. The Buy N Large corporation, a ubiquitous shopping chain, serves as the de facto government, with its CEO also holding the position of the American President. Humans have fled into space, where they are bombarded with advertisements on screens everywhere.

The film Wall-E, released in 2008, delivers a strong message about capitalism and consumerism, which may seem ironic given that it is distributed by the Walt Disney Company. The story is set in a post-apocalyptic future where the Earth has become uninhabitable due to excessive waste caused by rampant consumerism. The Buy N Large corporation, which is so widespread that its CEO is also the President of the United States, has led the remaining humans to live in a space station, surrounded by screens that constantly bombard them with advertisements. Wall-E’s commentary on consumerism is not limited to climate change but also takes a jab at the emerging trend of in-app purchases. The film’s criticism becomes even more pointed when the Buy N Large CEO declares their intention to “stay the course,” a phrase that was controversially used by the Bush administration.

Wall-E’s political and social commentary did not go unnoticed during the 2008 presidential election. Frank Rich pointed out the film’s relevance to the campaign in an op-ed for the New York Times on Independence Day that year. Rich notes that while children may not have recognized the real-world parallels, they were drawn to the film’s message of changing the world before it’s too late. In his article titled “Wall-E for President,” Rich praised the movie’s call to action, describing it as a subtle yet powerful invitation to remake the world.

Their shorts are experiments.

Pixar has revived the long-lost tradition of showing short cartoons before feature films. Since A Bug’s Life, they have entertained audiences with a few minutes of animation, often without any dialogue, exploring topics ranging from alien abductions and magic shows to lovestruck umbrellas. These shorts have been just as well-received as the features, earning nominations for Academy Awards and even their own art books and home video collections.

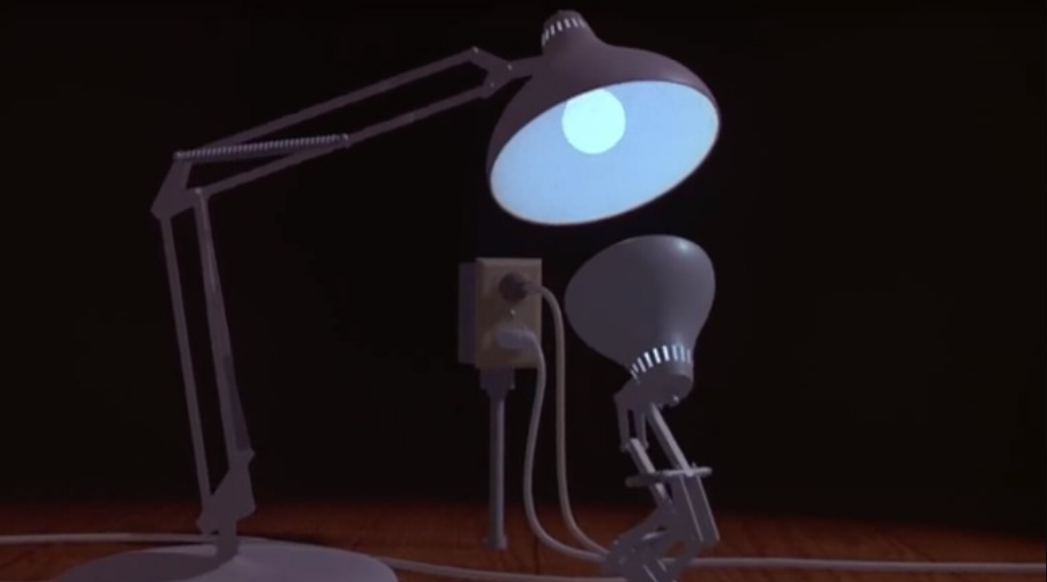

Pixar’s micro movies are not solely created for entertainment purposes. Beyond their surface-level appeal, these short films serve as laboratories for testing out new techniques and as training grounds for aspiring filmmakers. This practice has been ingrained in the studio’s culture since its inception. In 1984, director Alvy Ray Smith introduced “André & Wally B.” to demonstrate that computer-generated imagery was capable of producing basic character animation.

As Pixar gained popularity, they continued to draw inspiration from their experimental short films. “Tin Toy” from 1988 laid the foundation for what eventually became the blockbuster hit Toy Story. “The Blue Umbrella,” released in 2013, broke new ground in creating lifelike environments. However, the most recognizable Pixar short remains “Luxo Jr.” from 1986, which features the little lamp that has since become the studio’s logo. In 2011, Slashfilm published an in-depth article examining the production of “La Luna” and the various motivations and processes behind the studio’s short films. In 2017, Pixar formed a new division dedicated to experimental shorts, and their first creation, “Smash and Grab,” premiered before The Incredibles 2.